For decades, the U.S. food industry was a marvel of logistical efficiency, engineered to move calories from farm to fork as cheaply as possible. Today, that transactional model is being reshaped by a more strategic, resilient, and values-driven architecture: the

Food Value Chain.

This is not a buzzword. It marks a shift from treating each link as a cost center to organizing farmers, processors, distributors, and retailers as long-term partners aligned around shared goals. For industry professionals and engaged pro-sumers, this shift is increasingly a core competency. It is where commercial performance and social outcomes begin to reinforce each other rather than collide.

The Economic Imperative: The Farm Share Squeeze

The urgency behind value chains is clear in one sobering metric: the

Food Dollar. According to USDA Economic Research Service data, U.S. producers receive roughly

15–16 cents of every retail dollar spent on domestically produced food. The remaining 84+ cents—the “marketing share”—flows to processing, logistics, packaging, foodservice, and retail.

Where Each Food Dollar Goes (2023)

| Component |

Share of Food Dollar |

Primary Role |

| Farm Share |

~15.9¢ |

On-farm crop and livestock production |

| Marketing Share |

~84.1¢ |

Processing, transport, retail, foodservice, packaging |

That narrow farm share must cover fuel, seed, feed, labor, land, and debt service, leaving many producers financially exposed even as shelf prices rise. Value chains do not eliminate these constraints, but they are explicitly designed to improve how value is allocated. In well-designed local and regional models, producers can retain

60–85% of revenue through combinations of CSA programs and mission-driven wholesale channels.

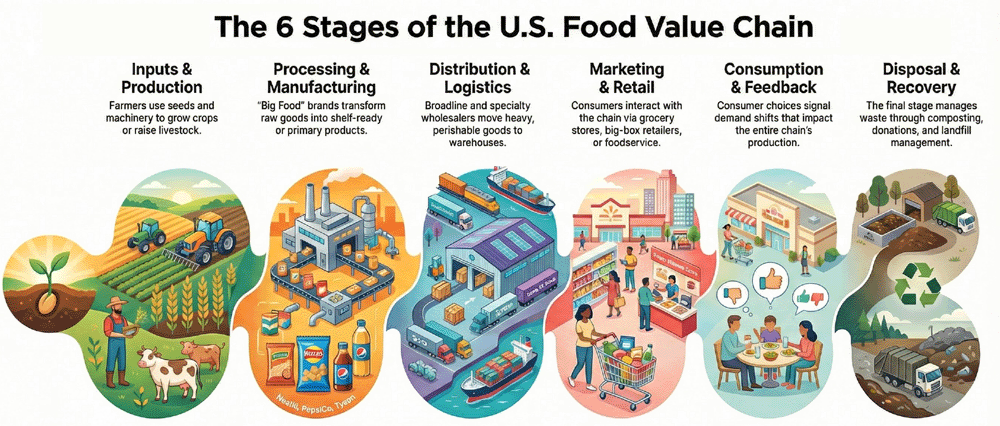

The “Value Loop”: A System with Feedback

Traditional supply chains are linear, optimized for throughput. Value chains operate more like a

value loop, where information and incentives flow in both directions.

- Farm: Produces raw ingredients to meet defined quality, stewardship, or certification standards.

- Factory: Converts commodities into finished or semi-finished goods.

- Movers: Manage cold chains, routing, and inventory risk.

- Sellers: Retailers and foodservice operators interface with consumers.

- Consumer: Choices around local, organic, or premium products send demand signals upstream.

- End: Waste reduction, donations, secondary markets, and composting.

In a functioning value loop, consumer preferences about provenance, animal welfare, or climate impact are captured at the shelf or online and transmitted upstream into production and procurement decisions. Over time, those signals influence land management, animal care, and how risk is shared across the system.

Retail Reality: High Volume, Razor-Thin Margins

Any discussion of value chains must contend with retail economics.

- Scale: Roughly 45,575 supermarkets operate in the U.S., each carrying about 31,800 items.

- Margins: Average weekly sales per store approach $712,000, yet net profit margins typically sit around 1–2%.

- Digital shift: Online grocery accounts for just over 7% of sales, but average online baskets (~$108) are more than double in-store transactions (~$45.70).

These constraints make it unrealistic to simply “pay farmers more” without changing how value is created and communicated. Value chains address this by offering differentiated products—rooted in transparency and trust—that some consumers are willing to pay more for, allowing benefits to be shared upstream.

Authenticity as a Strategic Asset

Many of the most successful value chains use

authenticity as a core operating strategy, deliberately preserving farmer identity from field to shelf.

- Country Natural Beef requires ranchers to regularly spend time in retail stores—often on the order of a couple of weeks per year—talking directly with customers about land stewardship, animal care, and product quality.

- Good Natured Family Farms brings together more than 100 farmers under a unified local brand, pooling supply and coordination to access regional grocery chains and generate multi-million-dollar annual sales.

These are not merely feel-good narratives. When well structured, such alliances can strengthen consumer loyalty, provide farmers with more stable contracts and improved income predictability, and give retailers defensible points of differentiation in a crowded, low-margin market.

The move from supply chains to value chains is a strategic response to intersecting pressures: margin compression, rising expectations for transparency, and the need for resilience across the food system.

For industry professionals, value chains offer a framework for more stable sourcing and brand differentiation. For the shopper, they provide a sharper lens—shifting the question from

“Is this cheap?” to

“How is value created and shared from farm to fork?”

Efficiency still matters. But the future of the food system will be shaped by how deliberately relationships are designed around transparency, long-term commitment, and shared success.