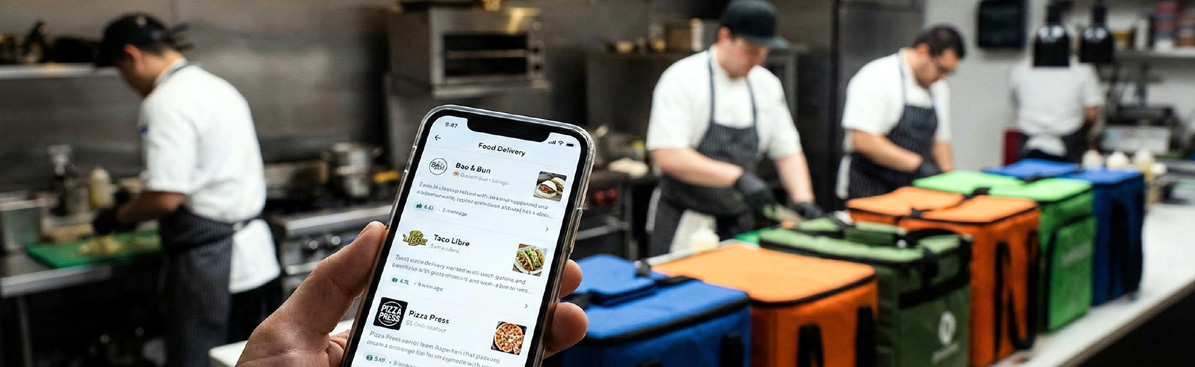

Food delivery apps are designed to make every listing feel like a distinct restaurant. In reality, many of those meals come from ghost kitchens—delivery-only operations running multiple brands out of the same space. If you care about transparency, quality, or simply knowing where your food is made, there are clear signals to watch for. These delivery‑only culinary operations have become the unseen engine of the modern takeout economy, quietly producing millions of meals without ever opening their doors to the public.

A ghost kitchen is essentially a production studio for food. No dining room, no signage, and often several brands running out of the same space. One line might be cranking out fried chicken for three different “restaurants,” while the next is plating tacos, wings, and breakfast bowls for a completely different set of brands. On your phone, they appear as distinct concepts with their own logos and reviews. In reality, they may share the same cooks, equipment, and suppliers. Ghost kitchens have grown because they’re built for the delivery era as they offer:

Lower overhead. No front‑of‑house staff or expensive real estate. A ghost kitchen can operate in a warehouse district or a shared commissary.

Fast launches. A new delivery‑only brand can go live in weeks. If it doesn’t catch on, operators can rebrand almost overnight.

Designed for the apps. Delivery platforms reward variety. Ghost kitchens can fill gaps — more wings in one ZIP code, more breakfast options near a hospital — without opening new restaurants.

Large chains have leaned in, too. Many “new” burger or chicken brands you see on delivery apps are actually side projects running out of existing chain kitchens. Third‑party companies also license celebrity or niche concepts to independent operators, who run multiple brands simultaneously.

The Branding Illusion

On delivery apps, the marketplace looks like a long list of independent restaurants. But behind the scenes, a single operator might be responsible for half a dozen of them. These virtual brands are engineered to win search terms like “smash burger,” “late‑night wings,” or “mac & cheese.” Their logos and names are built for thumbnails, not storefronts. A single kitchen might run a “local burger bar,” a “Nashville hot chicken shop,” and a “healthy bowl” concept — all from the same line.

Some consumers don’t care – as long as the hot food they ordered arrives hot and tastes OK they won’t think twice. For others, it complicates the idea of “ordering local” when the brand they’re supporting turns out to be one of many skins on the same operation.

Seven signs that a ghost kitchen has worked its way into a delivery app are:

-

The address is shared – Multiple restaurant names appear at the same location when you search the listed address.

-

No physical restaurant photos – The listing shows only food images or logos, with no storefront or interior photos anywhere online.

-

Unfocused, trend-heavy menu – The menu spans unrelated cuisines or mirrors whatever food trends are currently popular on delivery apps.

-

Duplicate menus across brands – Different restaurant listings use the same photos, descriptions, or items with only minor name changes.

-

Brand exists only in the app – There is little to no presence outside the delivery platform, and reviews rarely go back more than a few months.

-

Generic, keyword-driven name – The restaurant name sounds optimized for search rather than tied to a real place or identity.

-

Packaging doesn’t match the brand – Receipts, containers, or labels reference a different business name or appear inconsistent.

Some Possible Pitfalls

Being virtual doesn’t mean that the food isn’t good but it does introduce some challenges:

Brands change faster than inspection databases. A ghost kitchen has to follow the same health codes as traditional restaurants but when they fall short they can cycle through concepts long before public records catch up.

Nontraditional setups. Some operators use trailers, pods, or parking‑lot kitchens that can outpace permitting.

Shared facilities. Commissaries house multiple tenants sharing loading docks, cold storage, and sometimes prep space — which can amplify both good and bad practices.

Menus are increasingly algorithm‑driven. Search data and order patterns influence what gets created and promoted.

A few operators control a lot of volume. A city may show hundreds of “restaurants,” but a relatively small number of kitchen networks sit behind a meaningful share of them.

Brands can disappear and reappear overnight. A failed concept can relaunch under a new name with little friction.

It’s not all bad because some major chains that run ghost kitchens often do so with rigorous corporate QA. The issue is that both extremes look identical on the app. Ratings become the only visible signal, and a four‑star average can reflect great execution — or aggressive discounting and customer‑service recovery.